A machine is a physical system that can perform actions in the real world.

On this blog I've written a few posts about computing machines, which are physical systems for processing information. However there are many kinds of useful machine beyond this simple computer science definition. Bicycles, vacuum cleaners, cranes, escalators, and airplanes are just a handful of examples I encountered today. But what if all of these kinds of machine could be made out of just a handful of simple building blocks - like Lego bricks?

This was the seductive, yet ultimately flawed, theory that all mechanical engineering could be expressed in terms of compounds of simple machines.

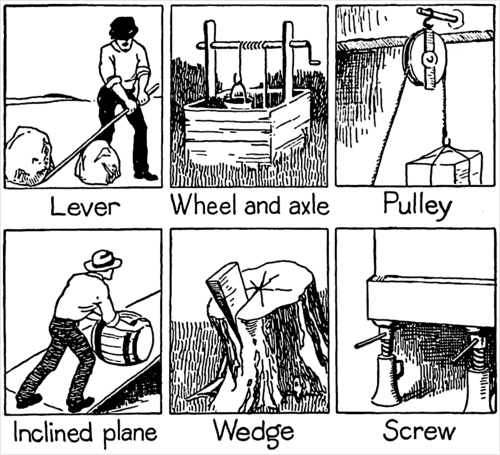

Hero of Alexandria believed there were five kinds of simple machine. A few contemporary lists (that claim to trace their taxonomies back to the renaissance) list six types (adding the inclined plane). The Wikipedia talk page on the topic contains some fascinating discussion about what the editors think does and does not count as a simple machine, for example they made a call not to include gears or springs in their list. Personally, I'm happy to take a fairly broad definition, whether there are 6 or 600 - it would still be a huge deal if it were just some relatively small number!

The German natural philosopher and simple-machine advocate Franz Reuleaux (he, by the way, listed 800 "elementary" machines, and built models of most of them!) does an especially good job of describing why this would be so exciting:

The peculiar condition consequently presents itself throughout the whole region of investigation into the nature of the machine that the most perfect means have been employed to work upon the results of human invention—that is of human thought without anything being known of the processes of thought which have furnished these results. Terms have been made with this inconsistency, which would not readily be submitted to in any other of the exact sciences, by considering Invention either avowedly or tacitly as a kind of revelation, as the consequence of some higher inspiration. It forms the foundation of the kind of special respect with which any man has been regarded of whom it could be said that he had invented this or that machine. To become acquainted with the thing invented we leap over the train of thought in which it originated, and plunge at once, designedly, in medias res.

He is saying that we should not take for granted that the "invention" of new machines is an opaque matter of human ingenuity or divine intervention. Instead we should be curious what kind of thought processes leads to such inventions. Reuleaux's approach was to try to create a sort of "language of invention" which could scientifically express all kinds of machine which could be built.

This might sound familiar if you have read about Leibniz's Characteristica Universalis - the idea that we could come up with a universal language of science to express every possible idea. Leibniz's project failed, but the same general approach of trying to create precise languages for expressing ideas can be seen in his body of innovations ranging from predicate logic to differential calculus. It's also similar to Alan Turing's construction Universal Computing Machine - a combination of simple rules which together can perform any computable function, and which was the precursor to the modern programmable computer.

I suspect that what all these cases have in common is that they take inspiration from Euclid’s elements. They are all motivated by some version of the optimism that: perhaps what Euclid did for geometry, we can do for all domains of human knowledge.

Back to mechanical engineering - if there were a finite number of simple machines, this would give us a general method for finding a machine to fit some set of constraints. All you'd need to do is define your constraints and then start searching over combinations of simple machine that might meet them.

My intuition is that for any sufficiently interesting set of simple-machines it likely turns out that the general question of whether some compound machine exists to fit some arbitrary set of constraints is undecidable, and the question of whether one exists which uses no more than N simple parts turns out to be NP-hard. However, the same is true of boolean logic, circuit design and of automatic mathematical proof, and the existence of both SAT-solvers, Electronic Design Automation tools, and proof-checkers, and all have been useful for their various fields. Proof checkers have also provided significant uplifts to the training and deployment of large language models to assist with frontier mathematics research.

So perhaps if we could enumerate a canonical list of simple machines then we might be able to get much better at building arbitrary mechanisms in the real world? I'm curious about this, but not so optimistic. I suspect that the question of whether a given machine actually works requires a lot more trial and error. Real machines are often imperfect, have various tolerances, and their various parts can end up interacting and interfering with each other in unexpected ways. As a result model-making, manual design and iteration all seem to me like they'd matter a lot in practice. But I'm not 100% sure about this! I'm keen to speak to some mechanical engineers and find out.