In yesterday's joint post with Adria he and I spoke about a surprisingly pernicious problem in the philosophy of computer science: we don't actually have a good account of what "implementation" is.

Implementation is one of the most fundamental relations in the philosophy of computer science. In fact, much of the field is dedicated to trying to deploy or make use of it. To give a “computational” account of a phenomenon is to describe abstract computational processes whose implementation is meant to explain it.

Computer programmers very quickly build up intuitions for what this relation is supposed to represent. It is found at a variety of levels of abstraction. You can read about an algorithm in a textbook and then write several different implementations of that algorithm in a variety of programming languages. Two computers with two different architectures are able to run the same computer program because their architectures both implement the same standard libraries required to execute it. What makes a given lump of matter a "computer" is that it is implementing some interesting computation. 1

There are many candidate accounts2 for this phenomenon, however all of the ones I have encountered so far seem to struggle one way or another to respond to the following argument and its variations.

The implementation arguments

These show up in the literature under a variety of different names including: "Putnam's realization theorem", "Searle's waterfall argument", "Searle's wall argument", "Putnam's rock example", and "Chalmers' rock example". The arguments are all slightly different (and notably Chalmers' version is a a case of him steel-manning3 Putnam's argument in order to then give a response). However they are all made in the same spirit and raise the same sketpical worry. As far as I can tell Hilary Putnam deserves the credit for being the first to write it up in detail. 4

These arguments are technical and hard to follow, the discussions they make span several papers and each person making them is leaning on different accounts of complex topics like modality, causation and semantic description. There is also a dynamic where every time a new version of the argument is introduced, new writers try to come up with better definitions of what implementation is to respond to them. 6

Below I try to sketch a general and simplified version of this argument, that covers its various use cases, while leaving the details down to the particular concept of implementation you want to discuss.

I realise this kind of move rarely has the intended effect, but selfishly, I also want to write a version like this up for three reasons:

- To give people a flavour of the general challenge raised, so they can decide whether it is worth reading the associated literature.

- To make it easier for friends and readers to send me papers they come across that are similar to this argument, as I am personally trying to collect variations of it.

- To make it easier to discuss the problem with people who haven't read all the relevant background.

My understanding of these arguments is they all make some version of the following points:

- To argue one system is implementing another, you need to construct a mapping between their states which preservers some set of properties. The set of properties choose to preserve will depend on the definition of implementation you choose.

- In order to construct a mapping from the states of one physical system to the states of another physical system we first have to decide what counts for a machine to be in a given state, and what counts for a machine to return to that state at a future point in time.

- The way we decide whether a machine is in some given state is by whether the matter which makes it up satisfies some description. (For example you might say a light switch is in an “off” state if it satisfies the description “the top part of the switch is lowered relative to the bottom”).

- So a mapping between states is possible if there is a mapping between descriptions of matter.

- But there is no easy way to restrict descriptions of matter to only "natural" ones, a description of matter is just some set of allowable configurations of that matter at a given time.

- So you can come up with arbitrarily many mappings this way! Matter is changing all the time, particles are buzzing around, isotopes are decaying, and particles are getting bombarded by radiation and cosmic rays. So for any big enough lump of matter inside your machine and any sequence of states you can come up with a description that says that the matter is passing through those states.

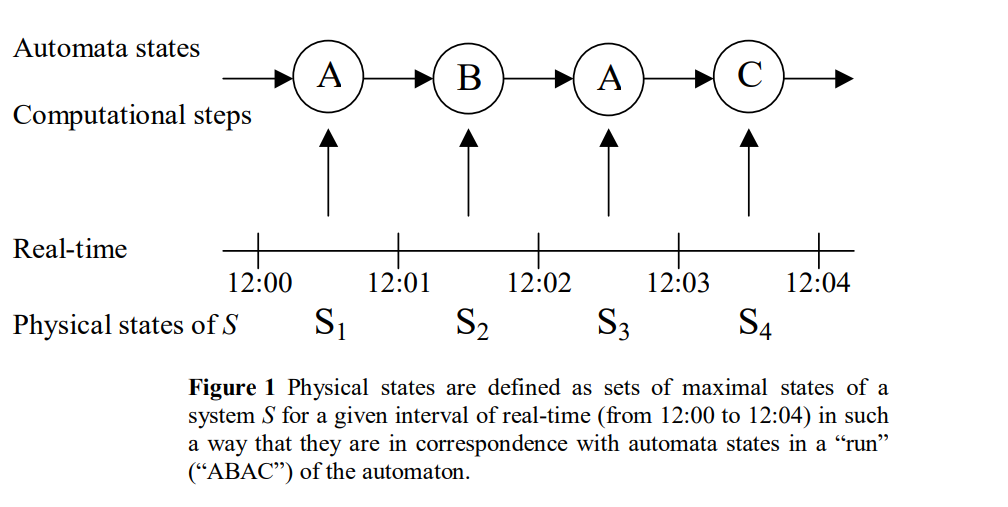

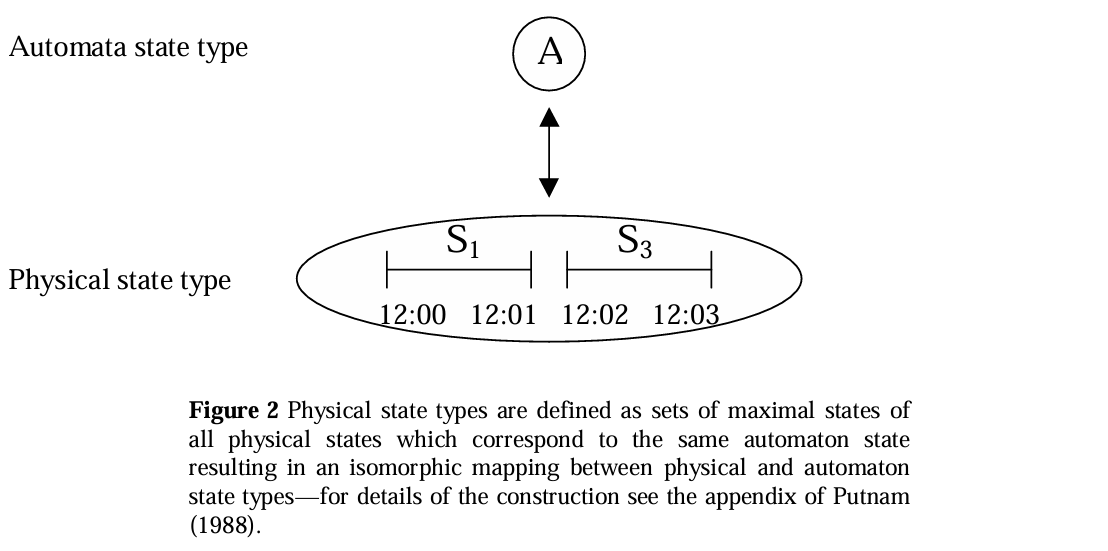

Matthias Scheutz provides some helpful diagrams for visualising one version of the argument in this paper which I think help illustrate the general point.

Links to papers on this topic

Early versions of the argument

- The appendix of Hilary Putnam's Representation and Reality contains a formal presentation of the argument, including working out details such as the assumption that the physical system is "non looping".

- John Searle's The Rediscovery of the Mind page 208 (or ctrf+ Wordstar) gives a readable, if fairly high level version of the argument.

Chalmers' and Copeland's responses

- "Does a rock implement every finite state automaton?" (Chalmers 1996) spends the first half re-stating Putnam's argument and steel-manning it against several possible objections. Chalmers then presents a solution based on considering counterfactuals on the internal structure of the automaton with a construction he names "Combinatorial State Automata". He closes with some open questions for his own construction.

- "What is computation?" (Copeland 1996) formalises Searle's version of the argument and then considers ways in which you can restrict allowable descriptions, including notably, trying to find a way to require that the "hard work" of the computation needs to happen "inside" the system being analysed rather than being done by the interpreting scheme.

- Various critics work through Chalmers' and Copeland's responses and construct new kinds of triviality arguments which still hold in spite of them, most notably Scheutz, who also does various bits of helpful exposition of variations of the argument:

- Implementation: Computationalism's Weak Spot (Scheutz 1998) makes a similar observation which I made above that Searle and Putnam's arguments are effectively using the same "trick".

- Do Walls Compute After All? (Scheutz 1998) shows that Copeland's suggested conditions are not strong enough to evade triviality arguments.

- Counterfactuals cannot count: A rejoinder to David Chalmers (Bishop 2002). Chalmers argues that it is not enough to implement the trace of an automaton, you also need to share that automaton's counterfactual behaviour7. Bishop pushes back on this assumption, and further shows that over a finite time every system meeting Putnam's original assumption implements the trace of every finite state automaton.

- What it is not to implement a computation: A critical analysis of Chalmers' notion of implemention (Scheutz 2012) and Three Challenges to Chalmers on Computational Implementation (Sprevak 2012) work through a series of objections to Chalmers' CSA construction

- Implementation and Indeterminacy (Brown 2003) Makes a very different argument against Chalmers' CSA construction - namely that they are too powerful and presents an argument that, if they existed, could compute things a regular machine could not.

Calls for alternative approaches

- The Embodied Mind (Varela, Thompson & Rosch 1991) argue that embodiment and world involvement are required to avoid "meaningless formalism" in the understanding of computational processing. This is similar to Putnam's view, though I'm curious whether it applies even without a community of language speakers, perhaps being accountable to some external environment turns out to be enough? I haven't read enough of this work to know whether they make this argument. Radical Embodied Cognitive Science (Chemero 2009) e.g. when discussing "emulation" in chapter 3 and "computability" in chapter 9 does explicitly discuss how representation of semantic content might work in computing systems - but does not explicitly link these to triviality of implementation worries.

- When Physical Systems Realize Functions... (Scheutz 1998) argues that in general state mapping views will always suffer triviality objections and that we therefore need to take an alternative approach.

- Causal vs. Computational Complexity? (Scheutz 2001) suggests an alternative approach following on from the above that suggests bisimulation as a stronger requirement than mere state mapping.

- Why Philosophers Should Care About Computational Complexity This long paper / short book contains a direct response to arguments like these along similar lines to Scheutz. Its statement is much simpler, as it doesn't try to come up with its own notion of implementation, it just notes that unless the mapping function itself is in some sensibly weak computational complexity class compared to the original algorithm supposedly computed then the mapping function is clearly doing much of the work. This also aligns with Copeland's original response in 1996. Finally its worth noting that this paper also offers related approaches to the problem of logical omniscience. Logical omniscience plays an explicit role in Putnam's original version of the argument.

- The Multiple-Computations Theorem and the Physics of Singling Out a Computation (Hemmo and Shenker 2022) Argues that techniques from physics, specifically statistical and quantum mechanics can be used to respond to Putnam's result

Other papers

Mostly a grab bag of papers I haven't yet read / understood:

- Levels of Functional Equivalence in Reverse Bioengineering (Harnad 1994)

- Triviality arguments against functionalism (Godfrey-Smith 2008)

- Computation, implementation, cognition (Shagir 2012)

- Miscomputation (Fresco & Primiero 2013)

- Against Structuralist Theories of Computational Implementation (Rescorla 2016)

- Computing Mechanisms Without Proper Functions (Dewhurst 2018)

- Triviality Arguments Reconsidered (Schweizer 2019)

- How to build conscious machines (Bennett 2025)

More recent books that discuss these arguments

I have not yet read any of these, except for parts of physical computation, so won't attempt to summarise their arguments.

- Milkowski (2013) Explaining the Computational Mind

- Shagir (2013) Has a chapter in Philosophy of Mind (ed. Andrew Bailey) Which is available online and discusses Putnam, Chalmers and Scheutz

- Piccinini (2015) Physical Computation: A Mechanistic Account

- Sprevak (2018) The Routledge Handbook of the Computational Mind This book's chapter on triviality of implementation arguments is freely available online and seems like it has some good overviews of them + an attempted response.

- Shagir (2022) The Nature of Physical Computation This book also has a chapter discussing triviality arguments that is freely available online.

-

One worry that I won't discuss here is the worry that the concept of implementation is chimerical. Perhaps each of these examples listed is in fact some quite different concept that only appears similar at the surface. For now I'll assume they are all the same. ↩

-

The SEP has a nice overview of different attempts to capture this concept. ↩

-

Being maximally charitable in order to do the opposite of straw-manning. See here. ↩

-

I suspect that in general these arguments turn out to be special cases of the sketpical argument Kripke makes in "Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language"5. Sprevak and Shagrir both note that an early version of these arguments also appeared in an example involving a pail of water by Ian Hinckfuss, but I cannot track down the original citation. If I understand correctly, Alan Turing's student Robin Gandy, also appears to have written about ways to figure out what counts as a "real" physical computation - but in the other direction of trying make precise the Church-Turing thesis. There is a discussion about some of his work here. ↩

-

Update - from further research Sprevak also makes this link in his 2005 thesis! I suspect the place to start to explore this link further is probably Wright & Miller (eds.), 2002 ↩

-

Overall it reminds me of the conceptual analysis of knowledge and the debate surrounding the Gettier cases. It's a distasteful analogy to make maybe, given how often the Gettier cases are maligned. I do think one sense in which it is helpful is that it shows it is better to speak of a family of skeptical arguments about our concept of implementation, rather than just one. ↩

-

Not core to the general question, but certainly relevant to its implications for consciousness - there is also this paper by Tim Maudelin which argues that counterfactuals cannot matter for whether something is conscious in the first place. ↩