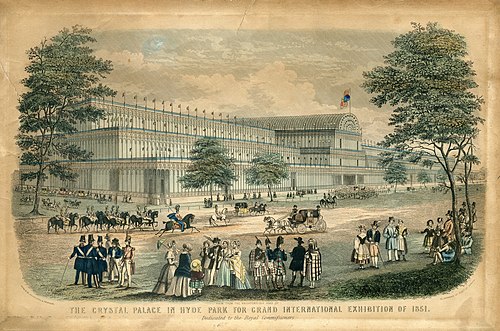

I first came across Perpetual Peace when reading about the London 1851 Great Exhibition. In particular I was curious what the main influences were for the strain of post-war cosmopolitan monumentalism that was on display at the crystal palace.

Mary Campbell Smith, the translator of the 1903 English edition of Perpetual Peace seems to make a direct link between the text and this 19th century utopian peace and industrial1 movements:

This is an age of unions. Not merely in the economic sphere, [...] but law, medicine, science, art, trade, commerce, politics and political economy—we might add philanthropy—standing institutions, mighty forces in our social and intellectual life, all have helped to swell the number of our nineteenth century Conferences and Congresses. It is an age of Peace Movements and Peace Societies, of peace-loving monarchs and peace-seeking diplomats.

... and slightly later in the same introduction

The Peace Societies of our century, untiring supporters of a point of view diametrically opposite to that of Hegel, owe their existence in the first place to new ideas on the subject of the relative advantages and disadvantages of war, which again were partly due to changes in the character of war itself, partly to a new theory that the warfare of the future should be a war of free competition for industrial interests, or, in Herbert Spencer’s language, that the warlike type of mankind should make room for an industrial type.

Aside from its role in influencing these events and movements, I think Perpetual Peace is interesting for three other reasons:

- It's a short and fairly readable text where you can see Kant grappling with the distinction between what is good and what is practical under adversarial conditions.

- It's a text where Kant uses the German word Personen to refer to both individuals, as well as collectives of individuals, in a sense very similar to contemporary hierarchical or scale-free theories of agency.

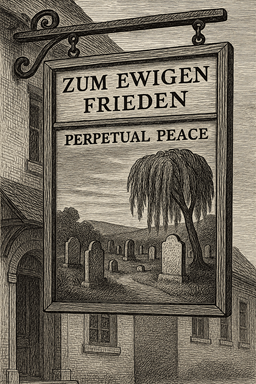

- It opens with a commentary on a striking and ironic image2 - of a graveyard with the caption "perpetual peace".

On the last point, I enjoyed seeing this kind of ironic humour and gothic passion in something written by the author of the Critique of Pure Reason. Aside from showing a bit more of his personality, the image also gives you a sense that Kant really is grappling with something that both feels difficult and alive to him. The image effectively says "the only true peace is in death". And the question Kant addresses is - is there any hope for a perpetual peace among nations, beyond this trivial sense?

What’s more interesting, however is the relationship between the first two points above. In particular I am interested in the extent to which the notions of acting in accordance with the good and the notion of collective agency go hand in hand in this text. In particular Kant makes a series of arguments about how the relationship between individuals and the societies they are in place constraints on the kinds of relationships that can exist between those societies.

Kant also seems to be treating states or societies themselves as a form or rational agent. Interesting questions to ask would be how far these analogies go. Presumably Kant did not think that states have an independent faculty of intuition or imagination - but perhaps he did think that certain other rational structures applied to their “thought”.

I’m not sure whether I’ll return to this text on this blog, but I thought it was worth calling out some surprising ways it relates to the general themes I’ve been writing about.

-

It's strange reading this stuff in hindsight and seeing just how much the role of industry in war as opposed to as a substitute for war is de-emphasised in the writings of this era. Arms dealers were even present at the 1851 exhibition with Alfred Krupp sending a giant steel cast for display! ↩

-

Kant only describes the image. I ran his description through an AI image generator. ↩